TWILIGHT ZONE: Tailspin of Terror

Portrait of a scary story, told thrice over decades apart, the bare bones of each telling as similar to each other as the airborne vehicles they depict. For once and future builders of this horror tale, the invoice for the parts list might read something like this: A terrified man, a turbulent flight, and certain doom that only he can see coming.

But while they each use established conventions of the horror genre to confront stigmas around mental illness, myriad differences between the three versions emerge and each diverges into its own unique route, for better or worse.

So which of these “Nightmares” stick the landing with clear-eyed insight about mental health and what we owe to each other? And which are best left to sputter through the forgotten corners of The Twilight Zone?

Chapter 1: TERROR TAKES OFF

“Nightmare at 20,000 Feet” first took flight as a 1961 short story by Richard Matheson. The author of cherished horror novels I Am Legend and The Shrinking Man among many others, Matheson reported that the seed idea of this story came to him in a hilariously mundane manner.

“I was on an airplane,” Matheson said. “I looked out the window and said, ‘Jeez, what if I saw a guy out there?’”

Matheson adapted the short story for The Twilight Zone’s fifth season in 1963. The episode features a brooding William Shatner and direction by Richard Donner, who later went on to direct Superman, a very different tale about an alien creature in the sky.

Twenty years later, Matheson adapted his story again for a bigger screen in Steven Spielberg’s 1983 movie adaptation. Star John Lithgow went big and refused to go home. And those bold choices were shaped and approved by George Miller, who directed the segment with his adrenaline-boosting aesthetic he’d flaunted 3 years earlier in 1980’s Mad Max.

Jordan Peele’s Twilight Zone reboot in 2019 eschewed the gremlin creature altogether in favor of a sinister podcast on a retrofuturistic player. Story credit went to reboot creators Jordan Peele and Simon Kinberg, as well as Marco Ramirez. Meanwhile, director Greg Yaitanes, whose credits include 30 episodes of House, knows a thing or two about main characters who piss everyone off by insisting he’s the only one who knows what’s really happening.

In the intervening years, the episode has been referenced and parodied countless times. It continues to seep into our collective consciousness with its claustrophobic premise, mordant black humor, and disturbing implications about how we fail to make space for the mental health of ourselves and others. To determine which of these tellings soar to the highest heights of horror, let’s examine two major aspects of each version: story and aesthetics.

Chapter 2: PANDA BEAR NIGHTMARE

The 1963 story, like the other adaptations, frames mental health stigma as the most terrifying monster to bedevil our protagonist.

William Shatner plays Bob Wilson, a man who had a mental breakdown on an airplane one year ago and afterward stayed at a psychiatric institution for six months. Now, he’s flying home. This is the only version of Matheson’s tale in which the main character has a loved one aboard the plane with him. Even the short story has Wilson flying solo. Here, his wife tries to accommodate him as much as possible. Their language offers a stark picture of where mental health discourse stood in the early 1960s.

WILSON: “I’m not sounding too much like a cured man, am I?”

JULIA: “But you are cured.”

A significant mental illness cured like the common cold? In-flight smoking isn’t the only outdated thing happening on this plane! Consider also this diagnosis which sounds a little slight by today’s standards.

WILSON: “Overtension and over-anxiety due to underconfidence...”

This over/under terminology feels inherently stigmatic. Sure enough, Wilson’s insecurities appear to worsen the more his wife tries to reassure him.

As Matheson did in his 1956 novel The Shrinking Man, the author frames the story’s fantastical concept in part as a window into toxic masculinity. Wilson feels unable to fulfill his patriarchal duties as husband and father. The state of his mental health has left him feeling small.

So much so that when he spots a humanoid on the wing, he retreats into self-doubt. The sightings persist. Of course, no one believes him.

To heighten the horror quotient and the interpersonal drama, Matheson portrays everyone as trying. Julia tries to support her husband, but fears that he’s not “cured” after all. The crew tries to acknowledge Wilson’s claim, but they coddle him instead. Wilson himself tries to report his observation while keeping the peace, but takes matters into his own hands when he realizes he has no true allies here.

Horror is rife with this kind of story: call it a “Cassandra narrative,” a “Chicken Little” story, or the “boy who cried wolf.”

The great pity of Wilson’s situation is that it’s his mental health history - as much as or possibly more than - the content of his claim that renders him untrustworthy in the eyes of his wife, the crew… and even himself.

The finest offerings of the horror genre often deal with powerlessness and isolation, and the 1963 adaptation is chilling in how it frames mental illness stigma as an invisible and insidious prison.

According to a study by the Mental Health Foundation last updated in 2021, nearly 9 out of 10 people with a mental illness feel stigma and discrimination negatively impact their lives. They also state that those with a mental health issue are “among the least likely of any group with a long-term health condition or disability to find work, be in long-term relationships, and be socially included in mainstream society.”

Wing-walking gremlin aside, the poisoned dynamic of Wilson’s situation is common even today.

Nevertheless, folks battling stigma find ways to prevail. In a bonkers move that surely would have seen his spine pulverized in real life, Wilson opens the exit door and vanquishes the gremlin once and for all. This outcome lives somewhere between triumph and tragedy. As is sadly common for people struggling with mental health, Wilson’s struggle is understood by him and him alone - and so is his victory.

Meanwhile, the episode’s aesthetics align in compelling ways to make us feel Wilson’s anxieties at every turn. Director Richard Donner amplifies the uncomfy vibes with stark shadows, lightning and thunder effects that provide a heightened campfire tale effect, and tense selections from the Twilight Zone music library. His most notable creative choices, however, involve this bad boy.

You may find this character design more campy than creepy, and you could be forgiven for thinking that what’s considered goofy-ass by modern standards was considered frightening six decades ago.

Turns out, even back in 1963, an actor in a Bigfoot costume was considered more than a little ham-fisted - at least by the original author.

Years later, when Matheson reflected on Donner’s execution of his script, the author candidly shared that he preferred the vision of Jacques Tourneur, director of “Night Call,” one of Twilight Zone’s creepiest outings, as well as horror classics Cat People and I Walked with a Zombie. Said Matheson: “I didn’t think much of that thing on the wing. I had wished that Jacques Tourneur had directed it, because he had a different idea…. Tourneur was going to put a dark suit on him and cover him with diamond dust so that you hardly saw what was out there. This thing looked like a panda bear.”

It’s not just the monster’s design that feels comedic. Its physicality and physics lead to absurd imagery. This creature ambles around on the wing with all the menace of a dad putting on the morning coffee in his kitchen. It shuffles about the wing fully upright, with no indication that it’s battling against high winds and G-forces to stay attached.

It’s uncertain whether Donner intended for these monster moments to play as comedy, or if he simply battled time and budget constraints as a first-time Twilight Zone director - he went on to direct six more episodes, so Rod Serling, at least, was pleased. Regardless of intent, the humor surrounding the gremlin doesn’t deflate the tension, but enhances it. The campy theatrics of the creature’s appearances make the situation come off as some kind of bad cosmic joke, a full-on existential prank show that has cast Wilson as its unwitting star. The utter ridiculousness of the visuals make these monster sightings all the more unbelievable, rendering Wilson that much more unwilling to believe himself, and unable to convince passengers of what he’s witnessed. It’s almost like the universe gaslights him, and does so with a cruel and twisted sense of humor. That we snicker along with this sadistic universe makes us the gaslighters, too, complicit in building Wilson’s invisible prison of mental health stigma. The monster might be funny, but the distress it inspires is no laughing matter.

Chapter 3: MAD MAXIMALISM

The script Matheson wrote for the 1983 movie hews closer to the simplicity of his original short story. Gone are the spouse and developed backstory of the protagonist, called John Valentine in this version. All we learn about Valentine is that he’s a computer engineer of some repute.

Whereas the ‘63 version centered on Wilson’s shortcomings as a family man, the ‘83 version emphasizes Valentine’s intellect as the source of his distress. After all, he stokes his death anxieties with current events and sobering statistics.

The movie paints this tech-head as simply too brainy for his own good. The early 1980s saw the rise of cable television and the 24-hour news cycle, with the launch of CNN in 1980. With the debut of the Apple II in 1977 and the IBM PC in 1981, the digital revolution was well on its way. Society at large began to grapple with information overload that would only mutate into today’s proliferation of social media fatigue, doomscrolling, and fake news. John Valentine appears to suffer from panic attacks brought on by a fear of flying, exacerbated by knowledge gleaned from books and media. This adaptation seems focused less on the mind of the individual and more on broader forces like the rise of the information age… or the breakdown of group dynamics in the face of crisis.

In response to Valentine’s mental distress, the plane’s crew and passengers are unhelpful, bratty, and downright hostile. In stark contrast to Shatner’s Wilson, Lithgow’s Valentine doesn’t bother with self-restraint. The “everyone is trying” ethos that turned the 1963 version into a pressure cooker, has now been replaced with all-out chaos. Miller favors aesthetics over story to make us feel the horror, which we’ll discuss more in a second, and that experiential approach certainly makes these events more immersive… but immediate thrills can come at the expense of lasting resonance. Miller presents a cold and glib worldview, where even our hero’s triumph feels empty.

Valentine confronts the monster, but doesn’t necessarily defeat it. The monster gives a devious finger wag and then flies away of its own volition. Did Valentine, somehow, scare it off? Or was the finger wag an indication that this attack went exactly as planned, perhaps as the first phase of a larger-scale assault? Did Valentine play a role at all in vanquishing his monster, whether it was imagined or real? It’s difficult to say. All we’re left with is Miller’s vision of a cold society that cares or understands little about the mental health of others. Furthermore, unlike the other versions, this adaptation invites us to poke fun at Valentine’s mental state, throughout the story and up till the very end, when he appears not at peace like Shatner’s character, but crazed with a newfound savior complex.

In a way, this adaptation’s disdain for how people behave in the throes of a mental health crisis is keeping in the spirit of the original story, but such a concentrated dose of cynicism feels somewhat slight. Horror writers often elevate their work when they take care to balance their darkest impulses with even a glimmer of positive insight about the human condition.

Aesthetically, the 1983 version flips the configuration of comedy and drama seen in the ‘63 version. Instead of straight-laced human characters and a humorous monster, director George Miller offers a collection of comedic human characters and a monster that invokes genuine terror.

The early ‘80s was a golden age of practical effects in horror, and George Miller’s realization of the gremlin shines alongside the era’s greatest highlights like American Werewolf in London and The Thing.

It’s likely the movie version gifted Matheson with the creature feature he longed to see the first time he adapted his story for the screen. The effects team led by Kevin Pike imbues the creature with a menace worthy of the Alien franchise, its claws, eyes, angled limbs, and slimy veneer coalescing into some kind of an unholy insect / dog / reptile hybrid. The nimble puppetry makes this creature feel hyper-immediate, its fixation on Valentine even more fully realized than the cat-and-mouse game between Shatner and his Bigfoot-like nemesis.

It’s not just the gremlin who goes to extremes. Everyone behind and in front of the camera dials the proceedings way past ten - and way past 20,000.

To amplify Valentine’s distress and isolation, Miller invites cinematographer Allen Daviau to throw everything into the kitchen sink here: hard blue lighting, fog, frenetic handheld camera shots with wide-angle lenses, and vertiginous shots stretched and squeezed in post-production.

Meanwhile, one of my favorite editing sequences in all of cinematic horror begins with this sustained shot of Valentine, a welcome reprieve from all the preceding chaos. The shot boils into dread the longer it holds on Valentine. It lingers for a tense 1 minute and 43 seconds as he slowly intuits that the monster lurks nearby. Very nearby.

Then the tension explodes with this fabulous subliminal gag. It appears that Kevin Pike’s effects team created some practical effects around John Lithgow’s likeness just for this blink-and-you-miss it moment, suggesting that Valentine and gremlin are one and the same, deepening Matheson’s grim portrait of mental health stigma: While Valentine sees the gremlin out on the wing, everyone on the plane perceives him as the vicious monster.

Miller also pumps this maximalist aesthetic into his Mad Max series as well as his upcoming feature, Three Thousand Years of Longing - geez, even that title screams maximalist. Matheson seems less convinced of its effectiveness here, but this high-anxiety cacophony is undercut with bone-dry humor that comes from its cavalcade of eccentric characters. Similar to caustic satires like Veep or Arrested Development, no one here, not even Valentine, is particularly sympathetic. So when Miller dials things up to 20,000, the domineering chaos lands as one big relentless farce. Whereas the universe’s cruel joke was on Shatner’s Wilson alone, here, the joke is on everyone because the joke is everyone. Miller’s maximalism makes monsters - and victims - of all of us. In this adaptation, Mental health stigma isn’t an A to B route - it’s a vicious all-consuming cycle.

Chapter 4: CONFUSED CREEPYPASTA

Whereas the ‘83 version stripped the story down to its bare essentials and left the narrative perhaps a little too bare, the 2019 story overloads its baggage compartment and sends this tale into a tailspin.

In “Nightmare at 30,000 Feet,” Adam Scott plays Justin Sanderson, an international journalist who finds a vintage-looking mp3 player that plays a podcast, apparently from the future, describing this very flight as one that mysteriously vanished. As Sanderson listens to the podcast, he works to stop the flight’s doomed fate, but in an unsurprising twist, he ends up causing the plane’s very disappearance.

This version riffs on our shared anxieties regarding 9/11, the 2014 disappearance of Malaysian flight 370, and other aviation tragedies and mysteries that have impacted the world in the 36 years since the last adaptation - not to mention the bad passenger behavior documented on our social feeds with increasing regularity. Removing the gremlin from this story is a worthy experiment, especially in this day and age when the passengers next to us feel like enough of an otherworldly threat.

And a sinister podcast feels like a snug fit for today’s growing interest in so-called “creepypasta” fiction: i.e., eerie urban legends that spread in the digital space.

But there’s so much fodder here for contemporary relevance that Ramirez and his co-writers get lost on their own flight path. Too many unanswered questions blunt the full horror potential of the podcast conceit. In the other “Nightmare”s, the gremlin’s origins stayed shrouded in mystery, but the monster still had a clear goal: destroy the plane. With no clear details given about the mp3 player’s origins or the motives behind the force who put it there, it feels less like a mysterious futuristic device and more like a clunky writing device.

Sanderson’s character journey feels similarly diluted. His efforts to convince everyone of the threats surrounding the flight appear half-assed at best. He never even gets around to telling anyone about the podcast. The script blocks his single attempt with a goofy bald joke.

Sanderson’s weak persuasive efforts make this group of onlookers come off as the most sympathetic out of the three versions, especially when the podcast pushes him to make a couple of groan-worthy xenophobic leaps.

So why is he stirring up discord on this plane at all? The story once again foregrounds our would-be hero’s mental health as a wedge between him and everyone else. When Justin first boards the flight, he struggles with his fear of flying that stems from his job-related PTSD.

However, the more he listens to the doomsaying podcast and the more in-flight chaos he creates, the more calm and self-assured he himself becomes, until he commits the fatal mistake of allying himself with the true monster onboard: a former pilot who intends to crash the plane in a psychotic attempt to wash away his own past. It seems Justin and this nefarious pilot are guilty of the same sin. Their inability to resolve their past dooms everyone else’s future. Justin pays the ultimate price for that sin when he and his fellow passengers crash land on an island, and they appear to beat him to death.

This busy episode gets lost in its own noise from several thematic through-lines that fight for attention. The script suggests that Justin’s key flaw could be his unearned confidence that he’d overcome his mental health struggles. Or his superficial defense of civility. Or his attraction to coincidence and omens. Or his confirmation bias that turns his fear of flying into a self-fulfilling prophecy. This adaptation exists in a liminal space where both an individual neglect of self care and social neglect of each other are put on trial. But the results are too messy to qualify as a multidimensional thesis.

The thematic clutter begins to clear away if the viewer entertains the theory that Justin’s imagination has run amok. Perhaps his PTSD led him to hallucinate both the podcast and the pilot, as a means to validate his worst fears and then conquer them. But those theories are dubious at best. Consider that the podcast feeds Justin a hard fact or two, like passenger’s names, that he’s unlikely to know himself. And if the mysterious pilot were a mere alter ego of Justin, then the cockpit video feed - given its objective nature - would show Justin hijacking the plane. To be fair, it’s possible that this pilot’s face was Justin’s true face all along. All told, this is the kind of puzzle-piece narrative that forces the viewer to do its heaviest lifting.

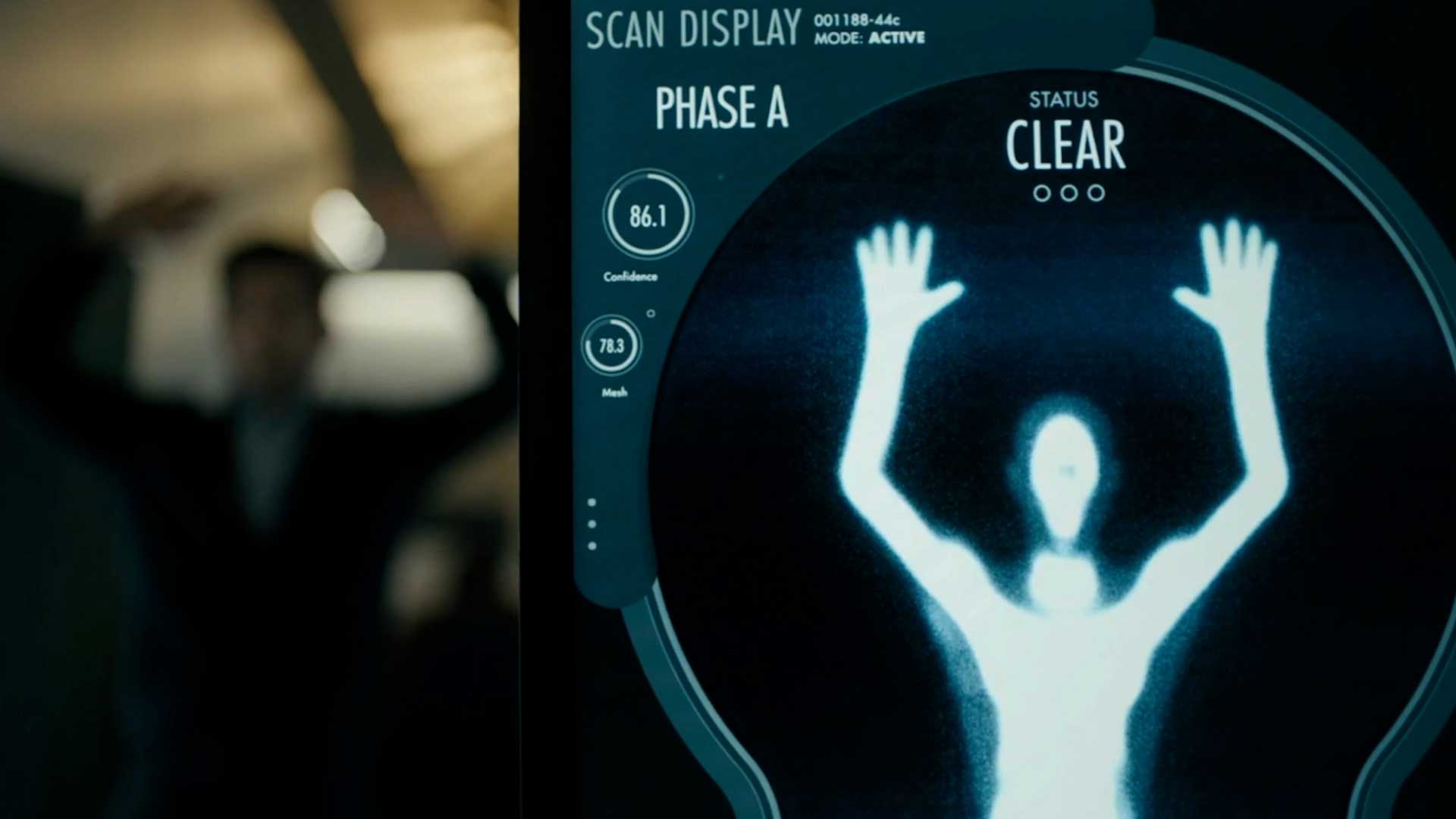

But do the aesthetics of this adaptation offer any impactful takeaways? If Miller’s version skews visceral where Donner’s veers psychological, the 2019 installment might be the most intellectual of the trio, designed more to be studied than felt. While this intellectual posturing is loaded into the theme-forward dialogue and story beats, it also lurks in the aesthetics. The episode features the visual earmarks instilled by show creators Jordan Peele and Simon Kinberg across both seasons of the 2019 reboot series: extreme close-ups, shallow depth-of-field, imbalanced compositions and most notably: circles, circles, circles!

The circle motif is cute and brand-appropriate. In fact, in some of the reboot’s more middling installments, you can pass the time just by playing a “spot the circle” drinking game with yourself. Jury’s out on whether this motif actually works as a mood-setter. On the one hand, the preponderance of round shapes, along with the aforementioned odd camera angles, can make us feel like something’s not quite right with this world, almost like the protagonist - and therefore the viewer - is unknowingly trapped in some kind of cosmic grand design courtesy of a mischievous, even sadistic, universe.

On the other hand, circles by their nature are not threatening.

In a breakdown about the psychological effect of basic geometric shapes, No Film School offers this insight: “Circles represent things that are soft, nonthreatening, natural... The continuous curve and rounded figure reminds many of us of things that appear in nature, like galaxies, stars, planets, clouds, raindrops, flowers, and waves… Circles have been used symbolically to communicate ‘completeness,’ ‘balance,’ and ‘endlessness’... the yin yang, the clock, the wedding ring.”

The circles of The Twilight Zone indeed feel soothing and pleasant, which works against the franchise’s decades-long promise of thrills and chills, and in this episode, works against Sanderon’s PTSD and the passengers’ resultant animosity toward him. “Nightmare at 30,000 Feet,” like the 2019 reboot at large, attempts to engage us on a philosophical level but falls short of grabbing us on a visceral or psychological level - despite cinematographer Craig Wrobleski’s thoughtful shot choices that do work to bring us into Sanderson’s feeling of isolation. Like many of the other creative choices at play, the visual style of this “Nightmare” shows thought and ambition, but overshoots the runway.

Chapter 5: LASTING NIGHTMARES

The finale of each adaptation contributes to its particular takeaway on mental illness stigma. After Wilson and Valentine confront their monsters, Matheson hints at potential vindication for both of them by ending on the physical eviden ce left by the gremlin. Nonetheless, that vindication is far from guaranteed. Wilson’s and Valentine’s similar stories are a powerful reminder that mental health stigmas are often so isolating that even when people achieve victories related to their mental health, few if any people in their lives can understand or empathize with those victories.

Amidst the vagueness of Sanderson’s story, his grim fate cautions us against the extreme lengths we might traverse in a mental health crisis to gain control of the uncontrollable. But his muddled story is devoid of suspense or narrative clarity. It’s a far cry from the 1983 version, which excelled at phenomenal practical effects and a potent if exaggerated depiction of mental and social unrest.

Ultimately, though, the 1963 version soars over its successors thanks to its pressure cooker approach that seethes with interpersonal tension and disturbing psychological underpinnings.

Whatever the decade, the story of a person in distress trapped aboard a plane with a monster that only he can see has gone from a sci-fi writer’s fleeting flight of fancy to a contemporary allegory forever etched into our collective consciousness. For as long as people respond to mental illness with fear instead of empathy, the legacy of “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet” will remain sadly relevant, in our own dark skies…. and in The Twilight Zone.